Architectural tourism is one of my priorities when traveling. However, there are undoubtedly some controversies involved in how certain structures are maintained.

One of the most controversial topics is façadism.

In the simplest terms, façadism – also known as facadism – refers to when the front-facing exterior (façade) of a building is preserved. This is independent what happens/has happened to the remaining part of the structure. For an example, let’s take this façade, located relatively near the eponymous food market in La Merced, Mexico City:

Mexico City might be a more nuanced place for facadism, if only because it is very prone to earthquakes. Indeed, there could be any number of occurrences as to why a façade would be salvaged; among those, historical preservation, unique beauty, and and a state beyond repair for the rest of the building are some of the more common reasons.

The concept of facadism has been controversial for years, though has become much more so due to the skyrocketing real estate prices in such cities as New York, London, and Sydney. Often availing of historic facades as a scapegoat for skyscraper projects that completely ignore the original building’s raison d’être, property developers are generally the last ones standing in a court battle with city officials and/or defiant communities.

To clarify, some of those facades might be on national lists of historic preservation, therefore cannot be bulldozed save for being in dangerous condition; that developers can do what they wish behind-the-scenes, so to speak, is just a facet of capitalism.

Façadism isn’t always done distastefully; though highly subjective, I tend to think the Greek Revival example serving as the entrance to the American wing in New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is a standout. But, if you tend to think it’s all an eyesore, you might be interested to know that there used to be a tongue-in-cheek award – the Carbuncle Cup -given out annually to the worst offender in the United Kingdom.

Now that we’ve learned a bit about facadism, I hypothesize that there are other aspects of architectural grievances that are overlooked, particularly in the face of tourism. Namely, I am referring to Shiro Syndrome, a phrase that I originally concocted while visiting Osaka, Japan in 2005.

Shiro Syndrome – in Japanese, shiro 城 means “castle” – refers to the reconstruction of castles (and temples, shrines, historic sites, etc.), frequently with contemporary materials. This is not specific to Japan, but being that it’s one of my most-visited countries, I can’t help but think about it, especially one moment in Osaka that started it all:

Although construction started on the castle in 1583, due to a combination of domestic strife and lightning destroying earlier versions, the current ferro-concrete structure was finished in 1931. Further repairs were completed in 1997; an elevator was added soon after.

Which brings me to the question…do you think the present-day Osaka Castle should still be considered historic?

The same could be asked of many of the pagodas in Bagan, Myanmar:

Bagan, which was the seat of an eponymous kingdom between the 9th and 13th centuries, saw the construction of hundreds of pagodas during that time. However, subsequent to a catastrophic earthquake in 1975, many pagodas were hastily renovated with modern technology; another earthquake in 2016 damaged many more pagodas, worrying historians and archeologists alike about how the repairs would be carried out.

UNESCO has even removed some sites from its World Heritage List due to a number of reasons. The most common of which involves redesigning or reinforcing a structure by employing contemporary methods. The consequence of this is the damage done to the building’s authenticity or structural integrity. Such is what happened with Bagrati’s Cathedral, located in Kutaisi, Georgia:

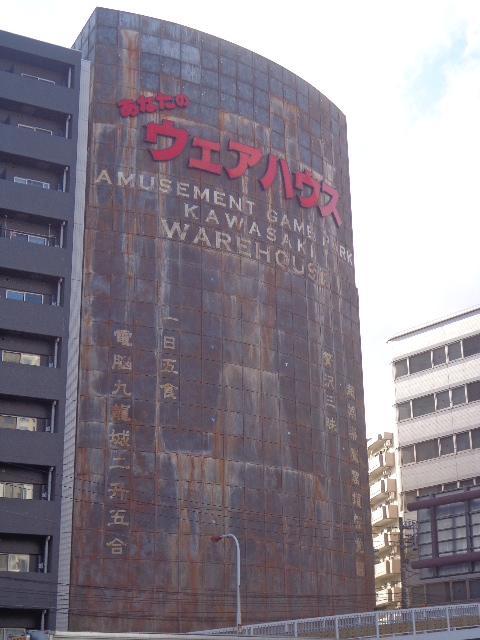

Finally, we have the now-obsolete Kawasaki Warehouse.

The entire concept of the building was to capture the essence of Hong Kong’s infamous Kowloon Walled City, a massive ghetto which was finally razed in 1994. If you’re curious about how it looked, the movie Bloodsport was allowed to film inside the labyrinthine Kowloon Walled City.

Obviously, they couldn’t capture the gestalt of the Hong Kong site. So then, what was the point? The Japanese version wasn’t in a good location, not to mention it was mostly design, as opposed to having games or activities to relieve visitors of their cash. It seemed doomed to fail from the beginning.

What is your opinion of façadism, and/or historical reconstructions?

Leave a Reply