Contemplating a trip to Tokyo and Osaka, but unsure about where to go between the two visits? Why not get a JR Hokuriku Arch Pass to appreciate the UNESCO World Heritage gasshou-style (合掌造り) architecture in Toyama?

Skip to: gassho, what’s that?

First, let’s briefly delineate the Hokuriku area. The three mainstay prefectures are Fukui, Ishikawa, and Toyama (sometimes, Niigata prefecture is included):

The area is undoubtedly known for seafood — crab, Japanese amberjack, mackerel, and trout come to mind — but also mountain temples, gardens, heavy snowfall, and lacquerware.

But access via international flights is rather limited. Even though Komatsu (KMQ) is the busiest one in the region, only China, Taiwan, and South Korea — reasonable choices — have nonstops. Toyama (TOY) is the only other Hokuriku Airport with scheduled, if less frequent, international routes.

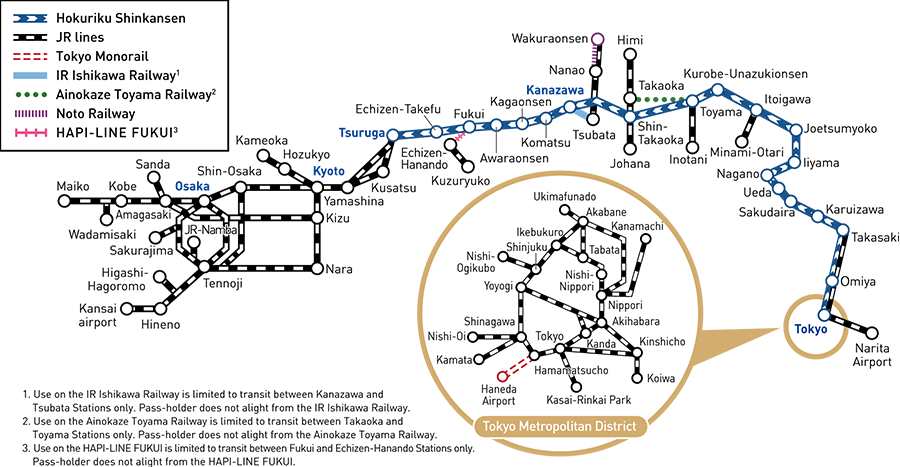

Consequently, the scope of validity of the Hokuriku Arch Pass is much broader.

Which Trains Can I Use?

- JR EAST Lines

- JR West Line

- Tokyo Monorail

- IR Ishikawa Railway*

- Ainokaze Toyama Railway**

- Noto Railway (between Nanao and Wakuraonsen stations)

- HAPI-LINE FUKUI (between Fukui and Echizen-Hanandō)***

- IR Ishikawa Railway is only available when passing through the section between Kanazawa Station and Tsubata Station (you can also use limited express trains)

- Ainokaze Toyama Railway is only available when passing through the section between Takaoka Station and Toyama Station (a liner fee is required if you wish to use the Ainokaze Liner rapid train)

- HAPI-LINE FUKUI can only be used when passing through between Fukui and Echizen-Hanandō.

For the visual learners (and map lovers like myself):

Plus, pass holders can also get discounts at a variety of attractions, restaurants, and stores … as long as you also present your passport.

Cost & Validity Period

Speaking of passports, the pass can only be obtained by those with the status of “temporary visitor,” so those with Japanese passports aren’t eligible.

The pass costs ¥30,000 for travelers aged 12 and up, and ¥15,000 for travelers aged 6-11. It is valid for seven consecutive days, midnight to midnight.

Where Can You Go?

Instead of showing my actual route like in other reviews, this time I will instead showcase a number of attractions accessible to those carrying the Hokuriku Arch Pass.

Kanazawa

Ah, the benefits of waking up early– no photobombers.

This is the massive torii (archways generally used for Shinto shrines) found at Kanazawa station.

Constructed as the outer garden of Kanazawa Castle in the 1620s, Kenrokuen only opened to the public in 1874.

It is widely known for its variety of flora, pine trees, tea houses, and two-legged stone lantern, the kotoji toro.

Higashichaya was an Edo period (1603-1868) neighborhood where geisha would entertain wealthy patrons and weary travelers. You might even see some folks donning attire from that bygone era.

Natadera (那谷寺) is a Buddhist temple founded in 717 and dedicated to Kannon, a goddess of mercy. What was particularly striking to me was the abundance of moss crawling up tree roots and stone lanterns, further heightening the forest bathing experience.

Since the shinkansen (bullet train) extension this past March, Natadera is even easier to visit. Alight at Kaga Onsen station, then board a Natadera-bound bus. There are also regular buses from Komatsu station.

Toyama city

Nagano city

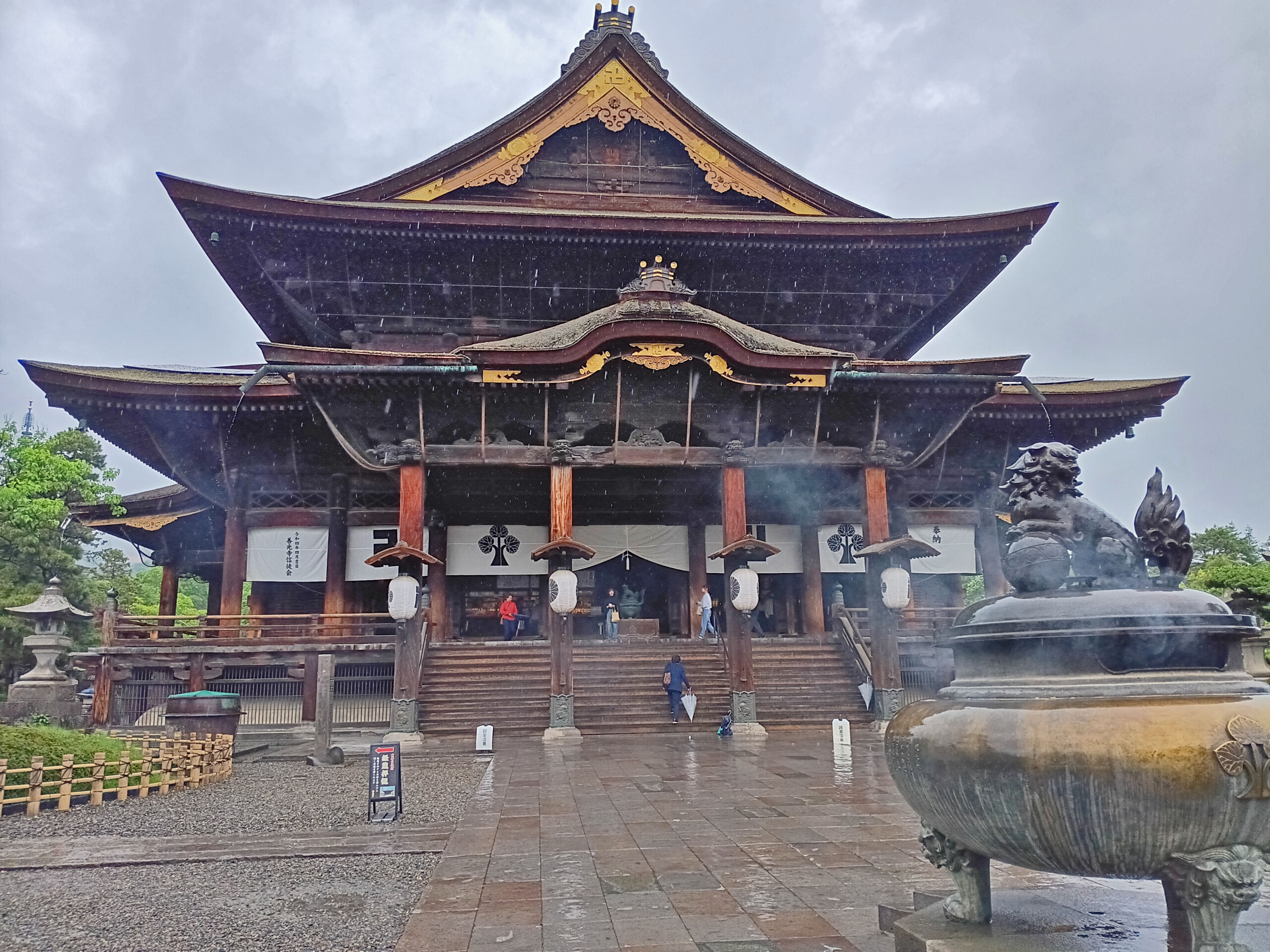

Zenkouji (善光寺), built in the 600s, not long after Buddhism was introduced to Japan, was the nexus of life in present-day Nagano city. It is best known for housing the first-ever Buddhist statue taken to Japan, which is only on public display every few years.

It is an expansive site, with numerous relics scattered throughout various halls. I particularly recommend checking out the main hall; photography isn’t allowed, hence why I don’t have a photo here.

For more than 300 years, (Nishinomon) Yoshinoya Brewery has been pumping out nihonshu made with alpine water.

That spherel hanging in the middle of the above photo is a sugitama, or cedar ball. When its green, that means new liquor has just been introduced.

Whereas many of the nihonshu choices were made with rice varietals from other parts of the country, I wanted to try one made with “Miyamanishiki,” or Nagano prefecture rice.

Another highlight was the liquor made with Nagano apple enzymes but not apple juice, eliminating the usual hyper sweetness found in the latter.

Osaka

Oh, did I forget to that? The JR Hokuriku Arch Pass is valid in both Tokyo and Osaka..boss!

Tsuruga

Finally, with Tsuruga having just become the last stop on the Hokuriku shinkansen earlier this year, I figured it might be worth pointing out a sliver of World War II history.

Sugihara Chiune, a representative at the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania, granted to Polish Jews nearly 6,000 visas to enter Japan. While they were able to board the Trans-Siberian railroad, they also needed a destination.

At this seaside spot in Tsuruga, those thousands of Polish Jews were able to get processed, and continue on to the major ports of Yokohama and Kobe.

The Gassho-style Architecture of Ainokura, Toyama Prefecture

Perhaps unusually, my first experience with anything Japanese — outside of video games — was a teppanyaki (what the U.S. calls hibachi) restaurant in Hawthorne, New York. I was 9 or 10, and simply put, was floored at the design of the restaurant.

The name of that restaurant — and possibly the first Japanese word I ever learned — was Gassho.

In Japanese, the original meaning of gasshou is “to place one’s hands together in prayer.” That gesture is what begot the design for the triangular thatched roofs of rural Toyama and Gifu prefectural homes.

Although a number of these houses have disappeared due to fires (the roofs are made of highly flammable thatch), or relocation due to infrastructural development, most were built in the middle- to late- Edo period (mid-1700s to mid-1800s).

Of course, it was no coincidence that heavy annual snowfall further influenced adoption of the roof’s design.

Seeing a gassho home up close might also have been my earliest travel goal. Thanks to Nanto City Tourism Association, I was even able to spend the night in one!

The name of my gassho minshuku, or private home doubling as an inn, was Nakaya.

I happened to have the place to myself, where in my room was typical tatami-style:

Accommodations included one of the best dinners I’ve had all year, and a fun breakfast with fiddlehead ferns.

Local musicians came by after dinner to perform the kokiriko, possibly Japan’s oldest folk song, which happens to be native to the region.

Access

Right, so the JR Hokuriku Arch Pass gets you close, but there is an extra charge to make the last leg of your journey to Ainokura gassho village.

From Shin-Takaoka bullet train (shinkansen) station, there are (infrequent) buses that stop right by the entrance.

Alternatively, you can use the rail pass on the JR Johana line to get to the eponymous stop, Johana station. From there, you have (infrequent) buses to Ainokura village’s entryway.

Considering the 7-day validity, and breadth of territory covered by the JR Hokuriku Arch Pass, I’d say go for it.

And just look at those gassho houses; I’m angling to go back in the winter when they’re in peak cozy form.

Leave a Reply